I LOVE science. From genetics to astronomy, neuroscience to botany, this branch of knowledge endears me with its concrete facts, equations, and straightforward answers.

Engineering? It’s cool too. As an engineering major in my second year, I’m in the process of learning a ton about what engineering actually is, and I’m enjoying it! You certainly have to know the science behind the technology you’re working on, but you also get to think creatively and innovate. On paper, you can have no limitations and let your designs go wild, but I’m learning that engineering in practice poses limitations that aren’t exactly fun to think about — cost and means of production for instance.

Now, philosophy of science? That’s a whole new level for me. I’m currently taking a philosophy and public policy class on the topic of neuroethics. The problems we’re examining look at how new developments in science and technology can be implemented, with all the ethical, legal, and moral issues that come with it. These types of complex issues enter a completely grey area where there is no right answer. Until taking this class, I generally avoided these types of topics because they’re out of my comfort zone; I think of them as being “fuzzy,” whereas my beloved sciences are concrete.

However, by taking this ethics class, I realized exploring these grey areas is essential. After all, if new discoveries in science are to come to any real world importance, they need to be applied in a practical, ethically sound way.

Let me give you an example. The most recent problem my classmates and I tackled was that of using neuroimaging technology to identify students who are at risk for committing acts of violence. Specifically, we were targeting both bullying in schools and more serious matters such as school shootings.

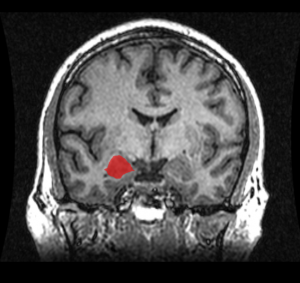

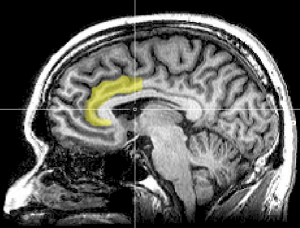

Taken from the Wikimedia Commons.

First, we examined the technology. (This part was really fun!) Recent neuroscience studies have examined the fMRI results of those who have committed various violent crimes (assault, homicide, etc.) and have been identified with various disorders (conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, etc.). Generally, results show the subjects to have decreased activity in certain regions of the brain as compared with the average person. These regions include the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), all of which are part of the limbic system, or the “emotional brain.” (Sterzer, 2009). These brain abnormalities may be why some children, adolescents, and even adults do not empathize with others or even derive pleasure for putting others in pain.

So clearly there’s an inherent difference between the brains of violent and nonviolent individuals; shouldn’t we scan everyone for these defects and have them treated? Well not so fast. There is vast range of what “normal” is for a human brain. Scans have also found those with abnormal brain structure and no tendencies toward violence whatsoever. On the flip side of things, there are many violent criminals who lack these abnormal brain structures. If a scanning requirement were put in place for schools, false positives would create unnecessary stigma and hassle, and false negatives would allow students at risk for committing violence to slip through the system.

On a related note, we need to consider that correlation does not equal causation. Just because a student may have a certain brain structure associated with violent tendencies, does not guarantee they will commit a violent act in the future. The brain is incredibly plastic, meaning it can change over time in response to experiences. An abnormal brain structure seen in a violent offender could be a result of actually committing the crime, or even a result of a negative childhood environment (Tsouderos, 2010).

Beyond reading through the studies published on neuroimaging, we also had to look whether implementation of scanning in schools is financially, ethically, and legally sound. Have any of you ever had a PET, CAT, or MRI scan? Those things are expensive, especially if you don’t have health insurance. And in the case of a state program, that cost is placed on the tax payer. How accurate and effective do these scans have to justify paying thousands of dollars per scan? Once we have identified students as having an increased risk for violence, won’t we need the resources to treat them? And how do we manage the information taken from scans? Which school personnel, medical professionals, and authorities will have access to this information? Is it right to force a student to undergo a scan?

In trying to find a solution, we ran into all of these questions and more. Ultimately, we decided against recommending using expensive neuroimaging technology (which, as cool as neuroscience is, it is still in its infancy) to combat violence in schools, instead looking at alternatives such as providing more resources for school programs to identify and treat mental disorders and promote mental health.

However, whatever decisions we reached concerning this problem or the other topics in the class (ranging from genetic modification of humans to what type of medical information can be admitted into court), the important part of this experience was the discussion along the way. Thinking about these types of complex issues has really helped expand my thinking and round out my education. In fact, I was so consumed by our ethical debates that I’m seriously considering taking a proper introductory ethics or philosophy class. And to all you students out there, I recommend you do this as well! Or if not ethics, just something outside of your major and outside of your comfort zone; you never know when you’ll discover a new academic love!