Introduction:

As I scrolled through YouTube to look for something to watch, I came across a Short (the term for the vertical, short-form video format on YouTube). The short was of a free diver swimming through a kelp forest and using a tool to scoop up all the sea urchins into a gigantic net. For some reason, I was instantly mesmerized by the video. I think it’s because 1) I think the ocean is awesome, and 2) the sounds of the video felt almost like ASMR. I went down the rabbit hole that day and watched the rest of this user’s content (sea urchin harvesting). There was something so satisfying about watching him gather a netful of sea urchins and use his tool to crack one open for the nearby fish. It appears the diver and the native fish have developed a symbiotic relationship: the fish leads the diver to the sea urchins, and the diver opens sea urchins for the fish to feast on. Watching all these videos made me wonder, “Is this really the only way we can control sea urchin populations, and what happened that caused the situation to get this bad?”

I knew for a long time about the lionfish problem. Funnily enough, YouTube started recommending lionfish videos to me. The diver uses a harpoon to impale lionfish and then places them in a bin. So then that made me think, “Is gathering these invasive species the only method of managing their populations?” It doesn’t seem that effective to me.

How are lionfish so successful as invasive or non-native species?

Background

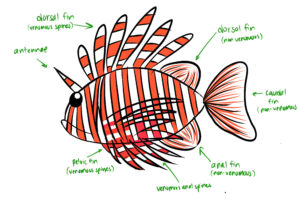

Lionfish, Pterois miles and P. volitans, are native to the warm waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and were introduced to South Florida’s coastal waters about 30 years ago (Norton & Norton, 2021). These fish are actually the first non-native marine fish introduced to the US’s Atlantic Coast and the Caribbean (Morris and Akins, 2009). They were common reef predators in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, so, with no predators to keep their populations in check, South Florida’s Atlantic coast provided the perfect conditions for these lionfish to thrive (Norton & Norton, 2021). Climate change also plays a role in the rise of lionfish in the Atlantic Ocean: the increase in ocean temperatures extends the lionfish territories north and south (Norton & Norton, 2021). Another leading cause of the success of lionfish establishing their populations is believed to be their broad diet, making them ecological generalists (Côté and Smith, 2018). From 2004 to 2010, lionfish populations rose drastically, increasing from 23% to 40% of the total predator biomass in the ecosystem (Green et al., 2012). By studying lionfish stomach content, researchers have found that “90% of the prey consumed by lionfish were small-bodied reef fishes from 42 species. Between 2008 and 2010, the combined body mass of these 42 species declined by 65%” (Green et al., 2012).

Control Efforts

Lionfish’s venomous spines provide effective protection against predators, but lionfish control programs have started across the Caribbean, which may successfully reduce the effects of lionfish at local scales within high-priority areas, such as Marine Protected Areas and fish nursery habitats (Green et al., 2012). The most common form of lionfish control is culling by locals or during organized tournaments (Côté and Smith, 2018). Numerous studies have shown that regular culling at target sites could significantly reduce populations and promote the recovery of native prey populations (Côté and Smith, 2018). Lionfish sizes have decreased due to targeted culling in various regions (del Rio et al., 2023). Unfortunately, not only is culling costly and physically demanding, but for culling to be effective, the amount of lionfish removed must be high: e.g., “35-65% annually at large spatial scales” (Côté and Smith, 2018). Another mitigation strategy is found in gastronomy—we collect lionfish recreationally or commercially for human consumption (Côté and Smith, 2018). It turns out, lionfish are delicious and nutritious (Morris et al., 2011b). Unfortunately, relying on native predators, particularly big groupers, is insufficient in controlling lionfish populations (Côté and Smith, 2018). One reason is that native predators aren’t as abundant as they used to be, and so these populations don’t consume lionfish enough to be effective (Paddack et al., 2009; Sadovy de Mitcheson et al., 2013). Researchers have thought of training native predators to consume lionfish (Diller et al., 2014). However, further research has found that training predators is unrealistic, so low predation on lionfish isn’t due to native predators being unaware that they could consume lionfish, but because of lionfish’s defenses against predators (the venomous spines) (Côté and Smith, 2018).

Conclusion

Based on the existing research, I would argue that introducing or developing lionfish as a potential food source for humans could aid in controlling lionfish populations. I think it’s super important that we educate people about the environmental problems of non-native species inhabiting ecosystems, and the efforts we can make to restore balance. I would think that research in mitigating lionfish effects on ecosystems would help in further research of non-native or invasive species in other habitats too!

Sources:

Côté, I. M., & Smith, N. S. (2018). The lionfish pterois sp. invasion: Has the worst‐case scenario come to pass? Journal of Fish Biology, 92(3), 660–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13544

del Río, L., Navarro-Martínez, Z. M., Cobián-Rojas, D., Chevalier-Monteagudo, P. P., Angulo-Valdes, J. A., & Rodriguez-Viera, L. (2023). Biology and ecology of the lionfish pterois volitans/pterois miles as invasive alien species: A Review. PeerJ, 11. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15728

Diller, J. L., Frazer, T. K. & Jacoby, C. A. (2014). Coping with the lionfish invasion: evidence that naïve, native predators can learn to help. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 455, 45–49.

Green, S. J., Akins, J. L., Maljković, A., & Côté, I. M. (2012). Invasive lionfish drive Atlantic coral reef fish declines. PLoS ONE, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032596

Morris, J. A., & Akins, J. L. (2009). Feeding ecology of invasive lionfish (pterois volitans) in the Bahamian Archipelago. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 86(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-009-9538-8

Morris, J. A. Jr., Thomas, A., Rhyne, A. L., Breen, N., Akins, L. & Nach, B. (2011b). Nutritional properties of the invasive lionfish: a delicious and nutritious approach for controlling the invasion. AACL Bioflux 4, 21–26.

Norton, B. B., & Norton, S. A. (2021). Lionfish envenomation in Caribbean and Atlantic Waters: Climate change and invasive species. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 7(1), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.016

Paddack, M. J., Reynolds, J. D., Aguilar, C., Appeldoorn, R. S., Beets, J., Burkett, E. W., Chittaro, P. M., Clarke, K., Esteves, R., Fonseca, A. C., Forrester, G. E., Friedlander, A. M., García-Sais, J., González-Sansón, G., Jordan, L. K. B., McClellan, D. B., Miller, M. W., Molloy, P. P., Mumby, P. J., Nagelkerken, I., Nemeth, M., Navas-Camacho, R., Pitt, J., Polunin, N. V. C., Reyes-Nivia, M. C., Robertson, D. R., Rodríguez Ramírez, A., Salas, E., Smith, S. R., Spieler, R. E., Steele, M. A., Williams, I. D., Wormald, C., Watkinson, A. R. & Côté, I. M. (2009). Recent region-wide declines in Caribbean reef fish abundance. Current Biology 19, 590–595.

Sadovy de Mitcheson, Y., Craig, M. T., Bertoncini, A. A., Carpenter, K. E., Cheung, W. W. L., Choat, J. H., Cornish, A. S., Fennessy, S. T., Ferreira, B. P., Heemstra, P. C., Liu, M., Myers, R. F., Pollard, D. A., Rhodes, K. L., Rocha, L. A., Russell, B. C., Samoilys, M. A. & Sanciangco, J. (2013). Fishing groupers towards extinction: a global assessment of threats and extinction risks in a billion dollar fishery. Fish and Fisheries 14, 119–136.

/*! elementor – v3.17.0 – 08-11-2023 */

.elementor-widget-image{text-align:center}.elementor-widget-image a{display:inline-block}.elementor-widget-image a img[src$=”.svg”]{width:48px}.elementor-widget-image img{vertical-align:middle;display:inline-block}