Introduction: The Problem with Wet Raincoats

Introduction: The Problem with Wet Raincoats

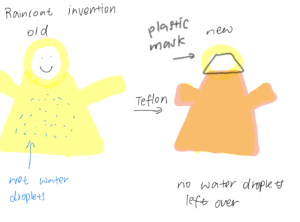

Imagine walking through rain and not seeing a single wet spot on your raincoat afterward. Most rain jackets protect you from getting soaked, but when the storm passes, you’re often left with dark streaks or damp patches on your clothes. These wet traces come from water that clings to the surface or soaks in slightly, making the coat look and feel less than perfect. Even the usual waterproof materials like nylon and polyester eventually show these marks, especially after you’ve worn them for a while.

Why Teflon Is Different

Teflon, also called PTFE, is famous for not letting things stick to it. That’s why you find it in nonstick frying pans and fancy lab gear. For raincoats, what matters is Teflon’s super-low “surface energy.” Think of surface energy as how much a material “wants” to attract water or let it spread. Teflon’s is about 18 millinewtons per meter, which is much lower than most plastics or fabrics. When rain hits Teflon, the water forms round droplets and rolls right off instead of spreading out or soaking in. This happens because the contact angle—the way a droplet meets the surface—is very large, often over 150 degrees. The bigger this angle, the less chance there is for wet marks to form.

If you zoom in on Teflon with a microscope, you’d see that its smooth surface, or even tiny nano-sized roughness added by plasma treatment, makes it even harder for water to “hold on.” This is similar to how lotus leaves stay clean in the wild—a trick called the “lotus effect”—since water picks up dirt as it rolls away.

Making the Material

There are a few ways to give fabric this Teflon power. One is to dip the fabric—usually nylon or polyester—into a liquid PTFE solution. After that, it’s baked at a high temperature so the Teflon layer sticks well. Another method uses a plasma — a kind of energized gas — to roughen the surface of the cloth before a fine Teflon spray is applied. This roughness on the microscopic scale helps water droplets sit up high and roll away easily. A third way uses a thin, expanded Teflon (ePTFE) layer, like you find in Gore-Tex. This ePTFE is full of tiny holes just big enough to let sweat escape but too small for rain, making the coat both waterproof and breathable.

How It’s Tested

To see if these new raincoat materials really work, scientists check how water interacts with the surface. First, they measure the “contact angle” by placing a tiny drop of water and seeing how round it stays. If it’s above 150 degrees, that’s a great sign. Next, they tilt the fabric to see at what angle the water starts rolling away. The lower the angle, the more water-repellent it is—ideally less than five degrees. High-speed cameras catch whether any water sticks behind as a trace. There are also tests for how well the fabric breathes, and how the coating stands up to being rubbed or folded, since nobody wants a raincoat that only works when it’s brand new.

What’s Been Found

When coated with Teflon, the fabric doesn’t just repel water in the lab—it stays free of wet streaks and dark patches even after you bend it or rub it. Expanded Teflon membranes work well, too, but sometimes a little water gets into stitched seams. Standard raincoat materials, like those with a simple polyurethane or PVC coating, tend to darken or show traces after rain because they let a little water stick or soak in. The Teflon designs solve this.

However, there’s a tradeoff. If you use a thick layer of PTFE, it can make the fabric nearly airtight, trapping sweat and making you uncomfortable. The best designs mix superhydrophobic coatings with a “breathable” textile underneath, so rain rolls off but you stay cool and dry on the inside.

Looking Ahead

New raincoats could do more than keep us dry; they could hide every sign that it ever rained in the first place. That’s what makes Teflon so promising for rainwear. There’s still work to be done, especially in making these materials eco-friendly and finding ways to repair or renew the coatings over years of use. Fabric scientists are trying things like self-healing polymers, special surface patterns made with lasers, and mixing Teflon with safer chemicals to make the ultimate “invisible trace” raincoat.

References

Barthlott, W. & Neinhuis, C. (1997). Purity of the Sacred Lotus. Planta 202, 1–8.

Wilkes, R. W. T. (1976). Surface Energy of PTFE and Its Copolymers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 55, 29–38.

Gore Inc. (2022). Understanding ePTFE Membranes. Technical Bulletin.