Has Plastoline made gasoline renewable and free?

@naturejab is a content creator who’s claimed to be able to recycle plastic into a fuel dubbed “plastoline” using solar-powered microwave pyrolysis for free. Having amassed over 76 million views on his flagship TikTok video1(that is, the one pinned to the top of his account), Julian Brown has his share of both fervent supporters who claim he’s revolutionizing the fuel industry and needs to hide from the government(see comment section), and skeptics who claim he’s “selling snake oil”.2

https://www.tiktok.com/@naturejab/video/7548988444844870942

Being a chemist, I’m not the type to take him for his word, that is, without the presence of reproducible analytical data confirming that he’s actually made what he says he’s made (which is nowhere to be found on any of his social media or on his personal website). But with plastic waste harming the ocean and planet at levels prompting international collaboration,3 part of me really wanted to believe that he had found a novel solution.

This article jabs into the nature of Brown’s venture by analyzing this pinned video in comparison with the literature surrounding the science: both what is promising about his project, and where his promises fail. And we get to learn some organic chemistry along the way!

So where does gas typically come from?

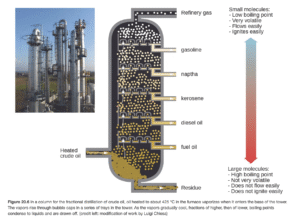

Gasoline and other fuels are derived from distillation, the process of heating a mixture in order to separate compounds based on molecular weight, of natural gas and crude oil (the gas and oil that comes straight out of the ground). Natural gas and crude oil are mixtures of molecules primarily comprised of carbon and hydrogen (aptly referred to as hydrocarbons). Heating crude oil until vaporization in a specialized distillation apparatus (like the one shown below), allows it to cool and condense into its constituent parts, more specialized hydrocarbon mixtures.5 For example, gasoline is one of these mixtures, consisting of hydrocarbons between 4 and 12 carbons in length.4

What does this have to do with plastic?

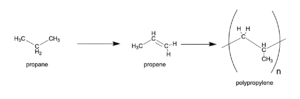

Many of the molecular mixtures separated out of crude oil can be (almost) used as fuel in various contexts. However, much of the mixture is separated into something that, well, can’t. Chemists probably worked day and night to try to turn this waste product into something profitable for their companies, but it wasn’t until 1951, when two chemists from Phillips Petroleum discovered a relatively easy way to transform propene into polypropylene, that the material plastic was born.6

The (basic) chemistry of plastics

We can describe plastic as a kind of molecule called a polymer (from the Greek poly-, meaning many, and –mer, meaning part). In the case of polypropylene, the “-mers” or as we say in chemistry, monomers (mono meaning one, and -mer also meaning parts) are propene, derived from a petroleum waste product: the gas propane.

Using some chemical sorcery beyond the scope of this article (but definitely worth looking into if you’re interested), we can prompt these monomer subunits to link together to form massive polymers—in our case, chains of hydrocarbon monomers from 50-1000 monomers long, creating the class of materials we know as plastics.

Many chemistry careers later, we have a wide variety of molecules derived from these original hydrocarbon chains that are used as materials in clothes, food packaging, cars, toys, electronics—you name it! And in context, this is seemingly awesome. We now have a material that can be used in both durable and delicate creations, one that won’t succumb to the elements, one that can last for hundreds of years7…. wait a second…

The Problem with Plastics

Millions of tons of plastic have been created, and the millions that have been discarded following industrial and consumer use are not readily biodegradable. This has unfortunately led to harming of both aquatic and terrestrial life, including, as scientists have discovered, humans.8

So how do we get rid of them?

To avoid killing the planet and everything on it, scientists got to work developing methods to break down these persistent polymers.9 Remember how when we originally created this plastic, we created chains of hundreds to thousands of monomers? Well, what if we took the plastic polymer, and heated it enough to vaporize and break down into smaller chains, made of only a few carbons?

This is the idea behind

Pyrolysis

A synthesis of the Greek prefix “pyr-” meaning heat or fire, and “-lysis” meaning “loosening”. 10 And in our case, we’d be “loosening” some of the bonds in this polymer by applying energy to them through heat, creating smaller hydrocarbon chains. So simply burning the plastics already dumped into landfills seems like it could be a solution to combat waste. Unfortunately, this has been shown to create persistent, toxic, products adding to the environmental harm of plastic.11

But under a vacuum, harnessing and carefully distilling crude hydrocarbon mixtures (like we did to the crude oil earlier) created by pyrolysis has been shown to yield fuel-like compounds (4-12 carbon hydrocarbons).12

And although the technology has not been applied on an industrial scale as of yet, using a continuous reactor setup using microwave radiation instead of traditional heating methods has been shown to be a less energy-intensive (and thus better for the environment) way to break down a variety of plastic polymers in this way.13 And funnily enough, continuous microwave reactor pyrolysis is the technique Julian Brown uses to create Plastoline– his plastic-derived fuel.

The Plastoline Process

Upon inspection, Brown’s process appears to be legitimate– that is, it appears to align with continuous microwave pyrolysis reactors shown in scientific literature13.

From left to right, these frames I grabbed from the video1 illustrate:

- the manual breakdown of a variety of plastic materials

- their addition to the reactor and subsequent vaporization

- collection of crude material from under vacuum (the pump is displayed beneath his right hand)

- distillation of crude material

- using propane(??)(non-renewable natural gas, -1 environmentally friendly points)

- and distilling some liquid over (at an unknown and unshown temperature)

What is the quality like?

When tested with an ‘octane rater’ on camera, with a model I found on Amazon14 (with zero reviews), the product receives an octane rating of 110. Assuming then, that this is in fact gasoline, that’s pretty great. Octane rating is a given fuel’s resistance to spontaneous combustion under high temperature and pressure, where a higher rating means a fuel is less likely to spontaneously combust and can thus be used in nicer, more powerful engines.15

Plastoline? Or Plastolies?

So is Brown’s Plastoline the future of fuel? To be honest, I don’t think so, at least not yet. While his setup appears promising and aligns at least physically with those appearing in the scientific literature, the lack of analysis of the resulting product means he could just be lying, as much as I personally don’t want to believe that. Apart from that, we are missing a lot of data that could tell us about the energy and chemical efficiency of this project, i.e. if it’s a viable solution for refining fuel from plastic in an environmentally-friendly manner. For example, we don’t know how much plastic-burnt waste product is being leaked into the atmosphere around his setup.

The gasoline you put in your car also contains many additives meant to increase the lifespan of your engine and help it run more smoothly4, which Plastoline, as a purported refined hydrocarbon mixture, does not contain (but possibly could in the future, with some modifications).

As a human being, I’m excited by the work that Brown is doing (along with millions of others), and I think it’s super cool that he’s created this whole setup, including welding his own reactor together, entirely in his parents’ backyard. More recent work of his shows him modifying minivans with jet engines to get a vehicle to supposedly run off of Plastoline, which is at the very least, really entertaining. But as a scientist, until I see some legit analysis come out of this project, I have to remain skeptical.

Citations

- naturejab. (2023, June 7). TikTok video [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@naturejab/video/7548988444844870942?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7519262020723688973

- Reddit. (2013, March 15). Is naturejab on YT real? Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/chemistry/comments/1d4jf3c/is_naturejab_on_yt_real/

- United Nations Environment Programme. (n.d.). Plastic pollution. https://www.unep.org/plastic-pollution

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (n.d.). Gasoline hydrocarbons. In Chemistry, manufacturing, and use of gasoline. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594140/#:~:text=The%20typical%20composition%20of%20gasoline%20hydrocarbons%20is:,*%20Upper%2Dcylinder%20lubricants%20*%20Detergents%20*%20Dyes

- OpenStax. (n.d.). 20.1 Hydrocarbons. In Chemistry 2e. https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/20-1-hydrocarbons

- American Chemical Society. (n.d.). Polypropylene: A landmark in chemistry. https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/polypropylene.html

- American Chemistry Council. (2010, March 17). History of plastics [Archived page]. https://web.archive.org/web/20100317004747/http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/doc.asp?CID=1571&DID=5972

- Welden, N. A. (2020). The environmental impacts of plastic pollution. In M. J. Castaldi (Ed.), Plastic waste and recycling: Environmental impact, societal issues, prevention, and solutions (pp. 195–222). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817880-5.00008-6

- Ellis, R. J., & El-Shall, M. S. (2020). Pyrolysis of polymers: Mechanisms and products. In M. J. Castaldi (Ed.), Polymer pyrolysis: Fundamentals and applications (pp. 123–145). Elsevier. href=”https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/pii/B9780128178805000086″>https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/pii/B9780128178805000086

- Zhang, H., & Wang, X. (2019). Catalytic thermal degradation of plastics. In Y. Sun & T. Wang (Eds.), Advanced polymer recycling (pp. 201–225). Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/pii/B9780128131404000133

- Online Etymology Dictionary. (n.d.). Pyrolysis. https://www.etymonline.com/word/pyrolysis

- Nature Catalysis. (2025). Sustainable chemical recycling of plastics. Nature Catalysis, 8(2), 101–110. https://www.nature.com/articles/s44407-025-00015-8

- Nature Scientific Reports. (2024). Plastic waste conversion via catalytic pyrolysis. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 71958. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-71958-3

- Oktis. (n.d.). Oktis portable analyzer: Instructions and product info. Amazon. https://www.amazon.com/%D0%BE%D0%BA%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%81-Oktis-Portable-Analyzer-Instructions/dp/B0FJ6DV2PF

- Kolb, D. (2010). Polymer recycling techniques. JSTOR, 27(2), 45–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44468563?seq=3