Saffron is the world’s most expensive spice. Its rich red stigmas and the difficulty in growing and harvesting it lend it the name of “red gold.”

Nowadays, saffron’s biggest use is as a spice for flavoring. Historically, saffron has been used as a medicinal plant, treating a plethora of ailments. Today we’ll take a look at the process it takes to grow and harvest saffron, and its medicinal uses– both historical and contemporary.

—

Saffron comes from the flower crocus sativus. The spice itself is made up of the bright red threads known as stigmas that grow as the flower blooms. I’ll be using the term saffron interchangeably with the flower from now on– but know that it isn’t the entire flower that produces spice.

Saffron corms are planted in late summer. You often use a tool known as a dibber to make a hole in the ground for the corm to rest. Corms look a lot like bulbs but aren’t the same. Although both are energy storage for plants, bulbs are a layered base from which a plant stem grows; whereas corms are solid, and are where the flower stem grows from.

By early October, saffron sprouts become visible. Saffron has thin, blade-like leaves that splay out once flowers bloom. The flowers themselves are a rich lilac color, and bloom for about three weeks. As the flowers begin to bloom, they can be picked and you can start to harvest saffron. Three stigmas grow in each bloom, and are best harvested in the middle of the morning on a sunny day, right when the flowers are open and fresh.

Pretty much as soon as the flowers are picked, you need to process it to remove the stigma. Waiting longer than a day will cause it to crumble, making it a time-sensitive process. Harvest season lasts around two to three weeks, and means all hands on deck for saffron farmers. It takes about 250,000 flowers for a single pound of saffron.

Once the strands are picked, they have to be dried. The spice is heated over a small fire. Heating it preserves both its color and aroma, but also shrinks its down to a fifth of its original weight. Once they’ve been processed and stored in the dark, saffron keeps for several years with no problems.

Because of how delicate the flower is, every part of the process is a manual task. The sheer number of blooms it takes for a usable amount of spice means an intense amount of labor.

—

So what have people used saffron for?

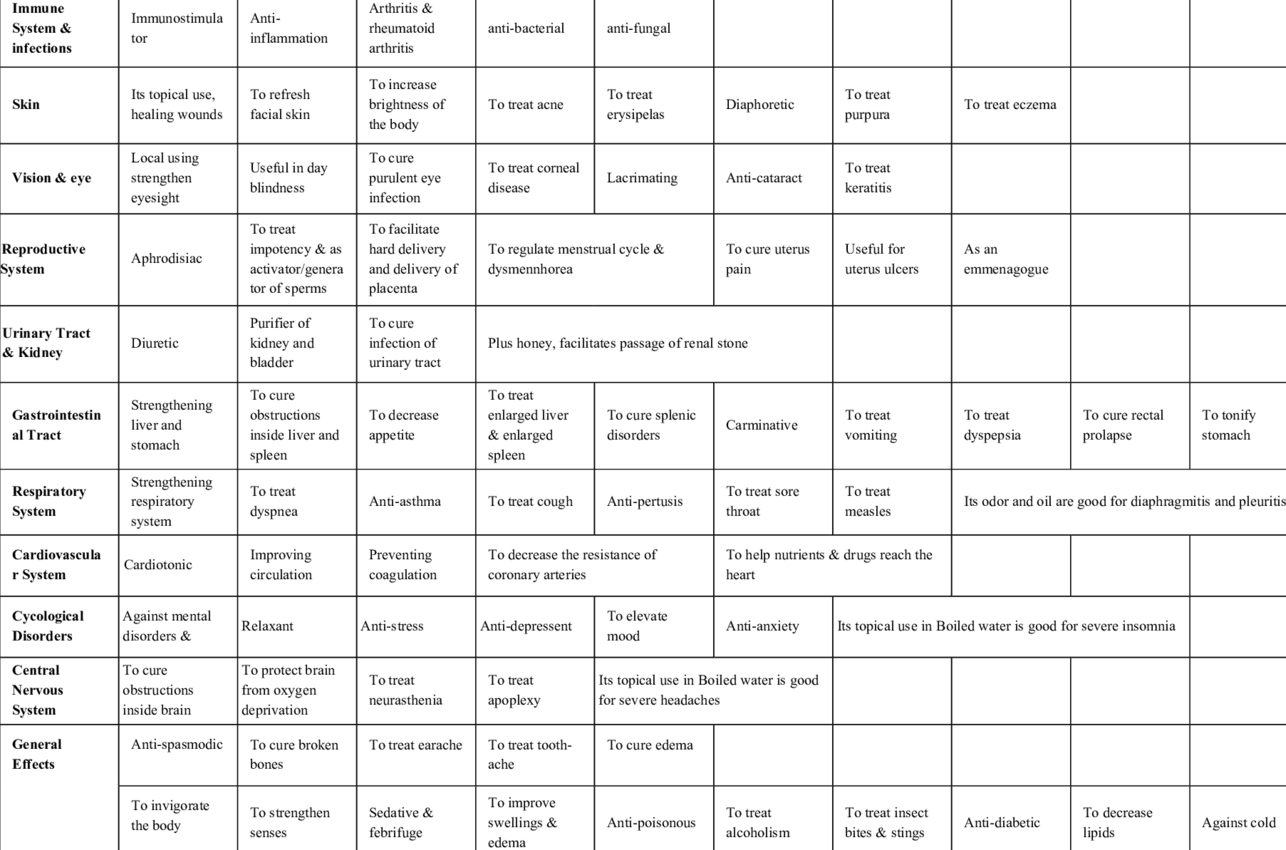

Saffron has been used by several nations as a spice, a dye, and perfume. Across the past four millennia, it has had the most number of applications across all medicinal plants, and has been used in the treatment of over 90 different conditions. The table below shows a list of several historical treatments involving saffron.

As you can see, the spice can help aid a plethora of conditions. How does it actually achieve this?

Let’s take a look at its chemical structure to find out. A chemical composition of saffron reveals over 150 individual components in the stigmas, but there are three dominant ones- crocetin esters, picrocrocin, and safranal. These are responsible for its color, taste, and aroma respectively, and all are contributors to its medical effects.

Crocetin esters have been shown to aid the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, endocrine, reproductive and immune systems. It’s believed this is due to its properties relieving oxidative stress, which occurs due to an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants in your system. Free radicals are oxygenated molecules with an uneven amount of electrons, which allows them to react easily with other molecules in your body. This propensity can set off large, potentially harmful oxidation reactions.

Oxidative stress can be a cause of several degenerative diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, epilepsy, and cancer. Antioxidants are able to neutralize free radicals, and safranal and crocin are incredibly effective ones.

—

Although medicinal usage of saffron has dropped off recently due to the advent of newer medicines, there’s been a recent resurgence in research about its medicinal effects. As scientists find more novel uses for the spice, however, climate change is rapidly reducing the viability of saffron farming.

Declining rainfall and a lack of irrigation networks has drastically reduced the amount of viable harvest. Take a look at Kashmir, where changing climate conditions have reduced harvest down to 13-15 pounds per year. For reference, forty to fifty years ago, the harvest from the same area was 90-110 pounds.

Saffron is more than just a spice to the people who grow them, it’s also their economy and culture. Over 19,000 families in Pampore, Kashmir are dependent on the spice. It’s integrated into cultural food and drink, and harvesting the stigmas is a family activity. It was once unimaginable for a saffron farmer to have any jobs outside of farming. But the reality of shifting weather patterns means that the labor-intensive practice of growing the spice is simply unsustainable.

Saffron is a rich and varied spice, with medicinal applications still being discovered. But if we don’t take better care of our planet, it’ll soon be impossible to continue growing.

Works Cited

Bashir, Aliya. “The World’s Finest Saffron Is in Danger of Disappearing.” _Saveur_, 4 June 2019, www.saveur.com/worlds-finest-saffron-is-in-danger-disappearing/.

Dai, Rong-Chen; Nabil, Wan Najbah Nik; Xu, Hong-Xi. The History of Saffron in China: From Its Origin to Applications. Chinese Medicine and Culture 4(4):p 228-234, Oct–Dec 2021. | DOI: 10.4103/CMAC.CMAC_38_21

“Growing and Harvesting Saffron at My Farm – the Martha Stewart Blog.” _The Martha Stewart Blog | It’s a Blog about Martha Stewart and Her Daily Adventures._, 17 Nov. 2022, www.themarthablog.com/2022/11/growing-and-harvesting-saffron-at-my-farm.html.

José Bagur, María et al. “Saffron: An Old Medicinal Plant and a Potential Novel Functional Food.” _Molecules (Basel, Switzerland)_ vol. 23,1 30. 23 Dec. 2017, doi:10.3390/molecules23010030

Khazdair, Mohammad Reza et al. “The effects of Crocus sativus (saffron) and its constituents on nervous system: A review.” _Avicenna journal of phytomedicine_ vol. 5,5 (2015): 376-91.

Nanda, Sanju, and Kumud Madan. “The role of Safranal and saffron stigma extracts in oxidative stress, diseases and photoaging: A systematic review.” _Heliyon_ vol. 7,2 e06117. 10 Feb. 2021, doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06117

Mousavi SZ, Bathaie SZ. Historical uses of saffron: Identifying potential new avenues for modern research. Avicenna J. Phytomed 2011;1:57-66